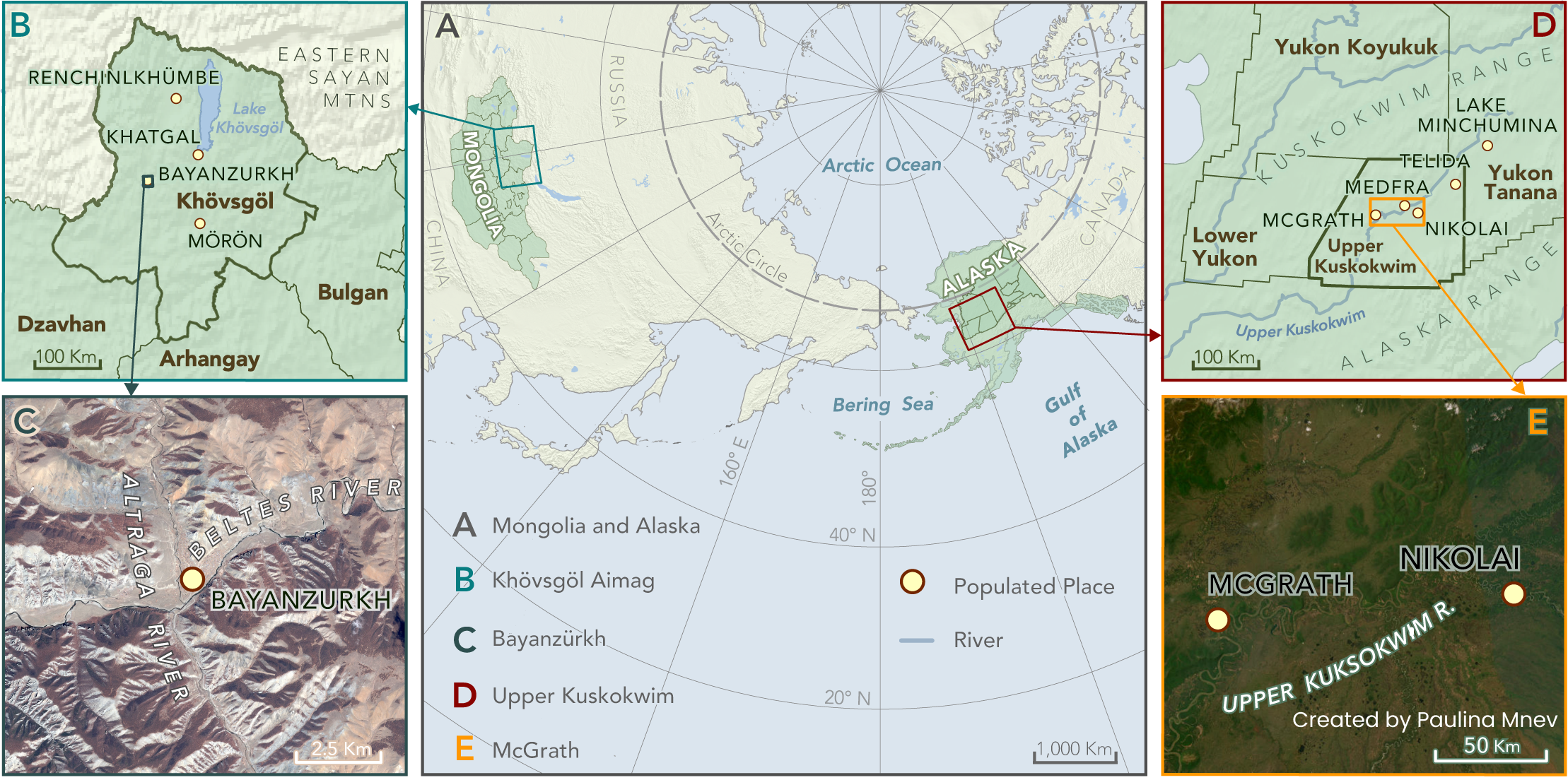

Map of Frozen Commons Project Study Regions

(A) Study area locations

(B) Khövsgöl Aimag, Mongolia containing

(C) Bayanzürkh Village (Satellite Pour l’Observation de la Terre (SPOT) image acquisition date: 12 May, 2022)

(D) Upper Kuskokwim Tanana Chiefs Conference subregion of Alaska containing

(E) McGrath and Nikolai Villages (Maxar image acquisition date: 25 May, 2011).

Study Regions

The selection of study regions for the Frozen Commons project reflects our commitment to fostering trust and collaboration with local and Indigenous communities. Our longstanding partnerships and ongoing work in these areas have guided our decision to focus on Tsagaannuur and Bayanzürkh soums in Khövsgöl Province, Mongolia, and the rural and urban communities of McGrath and Nikolai in Alaska, USA.

These regions share common challenges, including limited transportation accessibility, economic reliance on natural resource extraction, and the significant impacts of climate change. Both areas are experiencing increasing climate variability: while some regions face extreme warm periods, others encounter contrasting snow patterns, such as fluctuations between thicker and thinner snow depths.

By applying a collaborative framework, the project seeks to deepen our understanding of these shared issues while honoring the unique environmental and cultural contexts of each location. Through cooperation with local and Indigenous stakeholders, we aim to uncover innovative approaches to adaptation, resilience, and sustainable futures for these frozen landscapes.

Alaska

Alaska is warming nearly twice as fast as the global average, leading to rapid permafrost thaw, shifting vegetation zones, and changes in subsistence resources. Indigenous communities such as the Yup’ik, Inupiat, Athabascan, Aleut and Alutiiq are adapting their traditional livelihoods, combining long-held ecological knowledge with modern resilience strategies to face the accelerating impacts of climate change.

Upper Kuskokwim Region

The Kuskokwim River Basin in Southwest Alaska is one of the state’s largest watersheds, encompassing around 50,000 square miles of diverse subarctic landscapes. Flowing from the Alaska Range to the Bering Sea, the river traverses boreal forests, expansive wetlands, and tundra of the vast Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta—the largest delta in western North America. This mosaic of tundra, meadows, and boreal ecosystems provides habitat for rich biodiversity and supports the livelihoods of Indigenous Yup’ik and Athabascan communities.

The region’s subarctic climate changes from strong continental upstream to maritime at the delta. The watershed is characterized by discontinuous and sporadic distribution of permafrost.

The Kuskokwim River traditionally remains frozen from October through April, forming a vital transportation route for residents who travel by snow machine and truck between remote settlements. However, climate warming is rapidly transforming the Kuskokwim Basin. The river now freezes later and thaws earlier than in the past, with ice conditions increasingly unpredictable and unsafe. These changes mirror broader Arctic trends—altered hydrology, thawing permafrost, and ecosystem shifts—that deeply affect subsistence practices and community resilience. As part of Alaska’s Arctic system, the Kuskokwim River Basin stands as a critical site for understanding the intertwined impacts of environmental change and Indigenous adaptation in frozen landscapes.

McGrath

McGrath, located in Interior Alaska about 221 miles northwest of Anchorage and 269 miles southwest of Fairbanks. The City of McGrath is accessible by small plane year round, and in the summer by boats and barges. In the winter months they are accessible by long treks on winter trails and ice roads on the Historic Iditarod Trail system. It is situated along the convergence of the Takotna River and the south bank of the Kuskokwim River. It is the most upstream point where goodies can be delivered by large boats from the port of Bethel. Thus, McGrath, originally a seasonal Upper Kuskokwim Athabascan village, served as a hub, i.e. meeting and trading site for residents of Big River, Nikolai, Telida, Takotna and Lake Minchumina. In 1904, Abraham Appel established a trading post at the original site, and following gold discoveries in the Innoko District (1906) and Ganes Creek (1907), McGrath became the northernmost point on the Kuskokwim River accessible to large riverboats and developed into a regional supply center, formally established as a town in 1907 and named after Peter McGrath.

The town’s strategic role was reinforced by the Iditarod Trail, used between 1911 and 1920 by miners traveling to the Ophir gold districts. Flooding in 1933 and changes in the river course prompted relocation to the current site, where a store, airstrip, school, and FAA communications complex were later established. During World War II, McGrath functioned as a key refueling stop in the Lend-Lease Program. The town continued to grow with the construction of a high school in 1964 and was incorporated in 1975, with the federally recognized tribal government established in 1993. McGrath has an approximate population of 350, with about half the population being Indigenous Alaskan of predominantly Kochan-Athabascan descent.

Today, McGrath remains a regional hub. While the community offers various employment opportunities, subsistence practices continue to be central to local cultural life.

Mongolia

Mongolia is rarely associated with the Arctic. However, Mongolia ranks as the fifth country globally in terms of permafrost extent while experiencing climate warming 2.7% faster than the rest of the world. Similarities with the Arctic are especially evident in the Khövsgöl aimag, home for reindeer, yak and cattle herding communities with similar environmental and cultural forms as well as the common issues faced by communities.

Khövsgöl aimag

Khövsgöl aimag (Mongolian: Хөвсгөл) is the northernmost of Mongolia's provinces, named after the stunning Lake Khövsgöl, one of the largest and most beautiful freshwater lakes in the country. Established in 1931, the aimag initially had its administrative center in Khatgal until 1933, when it was moved to Mörön. The province is renowned for its diverse landscapes, ranging from expansive grass steppes in the plains and foothills to alpine tundra at higher elevations.

As the region with the largest share of Mongolia’s protected lands, Khövsgöl has preserved its natural beauty and ecosystems, remaining largely untouched by industrial development. With a population of around 140,000, the local economy and way of life are deeply rooted in pastoralism—a traditional form of livestock farming. The people of Khövsgöl raise a variety of animals, including cattle, horses, sheep, goats, camels, yaks, and even reindeer, reflecting a long history of human adaptation to the region's harsh environment.

Khövsgöl aimag is a key study area for the Frozen Commons project due to its unique snow, ice, and permafrost landscapes. Local communities have inhabited these frozen environments for millennia, developing rich traditional knowledge systems with a deep and intricate understanding of their natural surroundings. This knowledge, intertwined with their daily lives and pastoral practices, provides invaluable insights into sustainable coexistence with fragile ecosystems under changing climatic conditions.

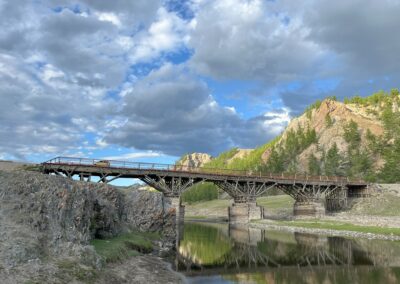

Bayanzürkh: A Heart of Mongolia’s Darkhad Depression

Bayanzürkh, meaning "rich heart" in Mongolian, is a district (soum) in Khövsgöl Province, covering an area of approximately 4,300 square kilometers (1,700 square miles). About 2,600 square kilometers (1,000 square miles) of this land is used as pasture. With a population of around 4,200, Bayanzürkh is home predominantly to the Darkhad people, known for their rich cultural heritage and traditional way of life.

Established in 1931 during the collectivization period of the socialist Mongolian People's Republic, Bayanzürkh's administrative center, Altraga, lies at the confluence of the Altraga and Beltes rivers, close to the Delgermörön River. Located 127 kilometers (79 miles) northwest of Mörön and 798 kilometers (496 miles) from Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, Bayanzürkh is also the first settlement encountered when entering the picturesque Darkhad Depression.

The Darkhad Depression is named after its Indigenous people, who have preserved their traditional nomadic herding practices for generations. The Darkhad tend to herds of cattle, horses, sheep, goats, camels, and yaks, which provide essential resources such as milk, meat, clothing, and transportation. Additionally, they sell sheep and goat wool, yak and horse meat, pine nuts, and wild berries to supplement their livelihoods.

Darkhad families move their herds between pastures four to six times a year, adapting to the seasonal changes in grazing conditions. Their portable homes, known as gers or Mongolian yurts, are lightweight and easy to assemble, made of wood frames covered in felt or canvas. Aerial images often reveal circular traces of previous ger locations, which remain visible for years—a testament to their sustainable nomadic lifestyle.

While the community remains connected to others by a bridge, local concerns focus more on the degradation of shared pastures, a pressing issue for the Darkhad who depend so intimately on the land for their way of life.

Tsagaannuur: Home of Mongolia’s Reindeer-Herding Dukha People

Tsagaannuur, meaning “white lake” in Mongolian, is a district (soum) in Khövsgöl Province, covering an area of 5,410 square kilometers (2,088 square miles). As of 2000, the population of Tsagaannuur was 1,317, primarily made up of the Darkhad people, with 269 identifying as Dukha, also known as Tsaatan or “reindeer-herding people.” The soum’s administrative center, Gurvansaikhan, is situated on the shore of Dood Tsagaan Lake.

Tsagaannuur was established in 1985 after being split off from the neighboring Renchinlkhümbe soum. It was originally part of a Soviet-era initiative to create fish processing infrastructure, which disrupted the traditional migration routes of the Dukha people. Families were forced to settle in the village, where adults worked in factories, and children were enrolled in boarding schools. After Mongolia’s peaceful democratic revolution in the 1990s, some Dukha families returned to their traditional reindeer herding practices, though many continue to migrate closer to the village during the school year for their children’s education.

The Dukha, or Tsaatan, are renowned for their deep connection to reindeer, which serve as more than just a source of food and transportation—they hold profound spiritual and emotional significance. These bonds are central to Dukha's identity and traditions. The Dukha primarily inhabit the Eastern and Western Taiga, remote boreal forests where reindeer provide milk, meat, and hides, as well as assistance with transportation.

The Dukha’s traditional dwellings, known as ortz, are cone-shaped tents similar to Native American tipis. In summer, ortz are covered with birch bark, while in winter they are insulated with reindeer hides. Today, 96% of Tsagaannuur soum’s territory is protected land, governed by local and national regulations that affect land use.

Tourism has become a vital source of income for the Dukha. Many families offer visitors handmade souvenirs, accommodations in their ortz, meals, and guide services. However, the Dukha face numerous challenges, including the rapid decline of their population—from 296 in 2000 to just 189 in 2021—and the impacts of climate change.

Global warming has severely disrupted Dukha’s nomadic lifestyle, with snow and ice that traditionally remained frozen throughout the summer now melting in Mongolia’s remote taiga. These changes threaten both their way of life and their unique cultural heritage.

Lake Khövsgöl

Although Lake Khövsgöl lies outside the Darkhad Depression, it holds significant importance for the livelihoods of the Darkhad and Dukha peoples. Revered as “Mother Sea,” the lake contains approximately 70% of Mongolia’s freshwater reserves, a critical resource that has justified the establishment of nature preserves and other environmental regulations in the surrounding drainage basins.

During the Soviet era, Lake Khövsgöl served as a vital connection between Mongolia and Russia, with its waters fostering cross-border interaction. To this day, the lake’s winter ice road offers residents the most direct route to the Russian-Mongolian border.

In addition to its strategic importance, Lake Khövsgöl is a popular summer tourist destination. Darkhad and Dukha herders often visit the lake during this time, providing services and selling traditional crafts to visitors, blending economic opportunity with cultural preservation.